Trained to Intimidate: The Racialised Logic of ‘Difficult Employees’ in Academia

Higher education institutions often pride themselves on being bastions of progressive thought and inclusivity. According to a recent report, UK universities have substantially increased their spending on EDI programs, with staff costs for EDI initiatives doubling over a three-year period to approximately £28 million per year, as mentioned in a February 2025 article in The Scotsman discussing university funding challenges.

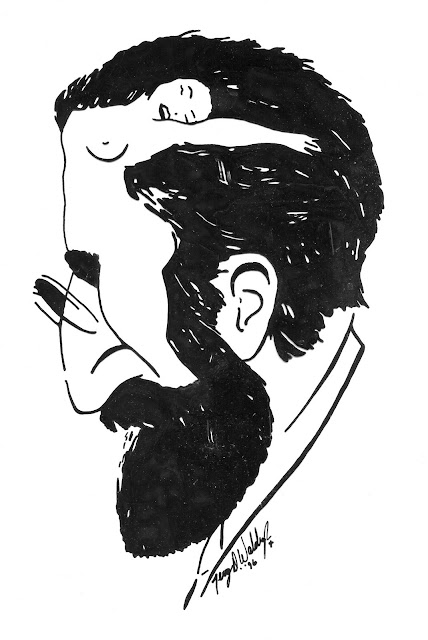

Beneath this veneer lies a troubling reality: the perpetuation of racist and sexist structures through multiple techniques that have already been thoroughly discussed on diverse platforms. I want to focus on one of those techniques today: management training programs, particularly those focused on handling “difficult employees.” Such training programs reproduce racism in junior management positions within higher education, creating institutional environments where employees from diverse backgrounds experience persistent marginalisation, display feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, and entrapment.

The Problematic Framing of “Difficult Employees”

The very concept of a “difficult employee” is laden with implicit biases that disproportionately target individuals from marginalised backgrounds. As noted by Dr. Marybeth Gasman, renowned in the field of race in higher education, faculty-hiring committees and their lack of diversity and racial bias training contribute to minority hiring problems in higher education. When institutions implement training on managing “difficult employees,” they often fail to recognise how the definition of “difficult” is culturally constructed and heavily influenced by dominant white norms.

The standards of professionalism in the workplace are heavily defined by what scholars Tema Okun and Keith Jones describe as “white supremacy culture” — the systemic, institutionalised centring of whiteness that explicitly and implicitly privileges white professionalism standards related to dress code, speech, work style, and timeliness. This framing is especially problematic because behaviours that may be labelled as “difficult” in one cultural setting might be valued and even respected in another.

Even worse, what is a unique quality that could otherwise be cherished and turned into a strength (for the institution itself, too) is undervalued if not completely dismissed. And how else do you think processes of marginalisation take effect? You mark people’s otherwise conventional behaviours as ‘problems’ (and discipline accordingly) and dismiss their unique strengths.

Training Programs That Deepen Racial Divides

Management training programs focused on handling “difficult employees” often teach techniques that exacerbate existing racial tensions rather than alleviate them. Cultural competence training, when not properly designed, can neglect the heterogeneity among members of cultural groups, encourage the use of race as a proxy for culture, and promote stereotyping. These trainings frequently provide standardised approaches that fail to account for cultural diversity and different interpretations of workplace behaviour.

Research shows that most unconscious bias training is ineffective. The problem lies in that increasing awareness is not enough — and can even backfire — because sending the message that bias is involuntary and widespread may make it seem unavoidable. When junior managers are trained to identify and address “difficult” behaviours without a nuanced understanding of cultural differences, they easily target behaviours that are simply expressions or results of cultural diversity. In the experiences many women of colour, personality traits that had gained them success also resulted them in being marked as difficult. Bear in mind that we’re not even addressing interpersonal dynamics such as issues related to rivalry or academic gollum-ness in this conversation.

Intimidation Techniques as Management Tools

Many management training programs teach techniques for handling difficult conversations that, when examined closely, amount to methods of intimidation and control. These include strategies for shutting down discussions, asserting authority, and managing opposition. They often also suggest plans for the most successful settings for intimidation, such as calling for a face-to-face meeting without providing a context (for the employee to fear for their future).

The core goal of bias training is typically to support people in acknowledging their own unconscious racial biases, with the understanding that awareness of how racism impacts behaviour and decisions at an unconscious level is the first step in changing behaviour. However, many studies dating back to the 1930s indicate that anti-bias training does not reduce bias, alter behaviour, or improve the workplace. When these ineffective trainings are combined with techniques that emphasise control over collaboration, the result is a workplace environment that reinforces existing power imbalances that they have experienced throughout their lives.

Familiar Experiences of Marginalisation

For employees from marginalised backgrounds, the intimidation techniques taught in management training are often painfully familiar. Blacks who manage to be hired as faculty can face racism in the work environment, including suffering from microaggressions, significantly higher rates of promotion denials, and abuse from their students, who resist and challenge minority faculty more than White faculty, according to multiple research studies. These experiences echo encounters many have had throughout their lives — with police, teachers, and others in positions of authority.

The tragedy is that these management approaches recreate traumatic power dynamics that many academics from marginalised backgrounds have spent their lives navigating. Instead of creating inclusive environments, such training reinforces the very mechanisms of oppression that have historically been used against these communities. In the context of institutionalised white dominance, workers of colour within organisations may experience race-based cultural exclusion, identity threat, and racialised workplace emotional expression, and be burdened by racialised tasks.

The Paradox of Institutional Belonging

The ultimate consequence of these management approaches is a profound sense of alienation among employees from diverse backgrounds. Studies have shown that racism affects students’ well-being, access, and performance in higher education. The same principles apply to employees, especially when management practices reinforce rather than challenge racist structures.

While Black students are overrepresented as victims of school disciplinary actions, comprising nearly half of school suspensions and suggesting systemic racism, they also complain about how they are treated differently in new student orientation, put into remedial courses, and discouraged from specific majors. These patterns continue into professional settings, where employees from marginalised backgrounds face similar forms of discrimination disguised as “professional standards” and “management practices.”

The paradox is clear: institutions claim to value diversity while simultaneously implementing management training that undermines the sense of belonging among diverse employees. Many White people deny the existence of racism against people of colour because they assume that racism is defined by deliberate actions motivated by malice and hatred. However, racism can occur without conscious awareness or intent. This unconscious perpetuation of racism through seemingly neutral management training creates an environment where marginalised employees never truly feel like they belong.

Beyond Training: Structural Changes Needed

Addressing this issue requires more than just reforming management training programs. Higher education institutions are failing to fully buy in to an equitable and just society for all. Public institutions should take responsibility for their historical participation in racism and discrimination, acknowledge who has benefited and who has been disadvantaged or harmed, and develop funded, mandatory antiracism workshops led by experts.

I don’t even know how I feel about the term “unconscious bias” but to stick to the officially recognised term, I suggest that if organisations want to address unconscious bias, they should raise awareness about its existence and effects through education and training programs. This will help leaders, employees, and stakeholders recognise their biases and develop strategies to address them. Policies and practices should be designed to be inclusive and culturally responsive to diverse needs and perspectives.

A Closing Reflection: Intimidation in Action

I would like to share a seemingly unrelated, but very relevant experience I had. It was 15 years ago, I was driving through Luton after picking up two hijabi friends -I was the third hijabi in that journey. It was in the first few months of my driving in the UK so turning right at that corner startled me for a few seconds. I didn’t make any mistake, although I turned with a delay, which was picked up by the police car cruising very close to me. The car stopped us, asked me to join them in their car parked behind us. They explained to me that I didn’t make a mistake, but I put the traffic at risk with that brief moment of hesitation. They checked my address and driving license and explained that it was acceptable for me to startle in the first few months of driving in the UK, where the traffic runs in reverse. Yet, they weren’t letting me back into my car. It wasn’t exactly clear why they weren’t explaining any of this while I was still in my car, either. Instead, they were increasing the tension, using an angrier body language with a heightened voice every second. I was feeling, with much certainty, that they were expecting me to act in a certain way. After several minutes, I sensed -and only sensed- that they wanted to see that they put fear into my heart. Upon this sensation, I decided to act very frightened and act very ‘indebted’ to their pardon. The sense I had was that these three young policepeople had completed their training in ‘intimidation’ just very recently, and decided to exercise this new knowledge on a visible Muslim. These were only senses, just like my ‘strong sense’ that our hijabs had made us easier targets.

That is exactly how management training techniques and the everyday experiences of marginalised individuals. The escalating tension, aggressive body language, raised voices, and expectation of submission are the very tactics often taught to managers when handling “difficult employees.”

For marginalised individuals, these are not merely theoretical management concepts but lived realities they have faced throughout their lives.

When these same techniques appear in workplace settings, they trigger recognition of a very familiar pattern of oppression.

The performative submission described — having to “act very frightened and act very ‘indebted’” — mirrors exactly what marginalised employees often feel expected to do in workplace contexts where management has been trained to use intimidation as a control tactic. A person of colour colleague, from a sexual minority background, once told me how they always ‘pretend’ to admire their line managers to get out of those situations. Our focus is too precious to sacrifice in political battles (and these are nevertheless part of our everyday political battles). Our options are often either to dedicate ourselves to correcting the micro and macro racisms or to focus on our own work. They chose the latter. “Their ego is my Lego”, they explained. They were channelling the survival strategies they had developed over decades into their workplace. This is the essence of the paradox: the very techniques taught to managers as tools of effective leadership are the same techniques that ensure marginalised employees never truly feel they belong within the institution. They feel trapped, rather than safe, genuinely welcomed, or included.

Conclusion

The reproduction of racism through junior management training in higher education represents a significant barrier to creating truly inclusive institutional environments. It is almost as if, as the academics from margilanised backgrounds stay in academic institutions, they encounter new faces of racism, in renewed and even intensified ways. By teaching managers to handle “difficult employees” without addressing how racial and cultural biases shape this concept, these programs perpetuate systems of oppression under the guise of professional development.

True institutional change, for those who have every good intentions to do so, requires a critical examination of how management practices reflect and reinforce dominant cultural norms. Only by acknowledging the ways in which categories like “difficult employees” are racially coded and by developing approaches that value rather than suppress cultural diversity can higher education institutions begin to create environments where all employees genuinely feel they belong. This transformation demands not just reformed training but a fundamental reconsideration of how institutions understand professionalism, difficulty, and belonging in diverse workplace settings.

Comments

Post a Comment